Photographing everything and taking time to look

In a 2016 New Yorker article, In the Future, We Will Photograph Everything and Look at Nothing, author Om Malik wrote that:

we have come to a point in society where we are all taking too many photos and spending very little time looking at them.

It’s true. We take so many pictures and we often won’t or don’t get a chance to review them. According to my platform stats, I currently have 1543 pictures in my Instagram feed and 36,837 pictures in my Google Photos storage.

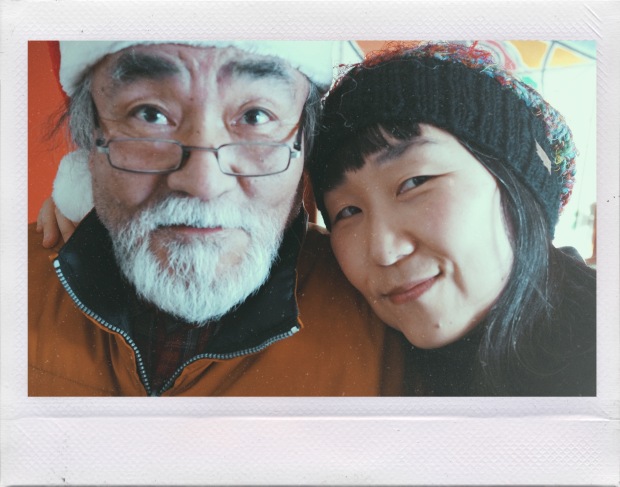

My dad just passed away suddenly and unexpectedly last week.

In preparing for the memorial service, I asked Google Photos to make an album of my dad. And Google’s creepy but magical face-searching algorithm compiled all these pictures of my dad snapped on our phones, Sony NEX (the Alpha-series precursor), and even an old Nikon compact something-or-other, from 2006 to last month, drawing from 3 different people’s gigabytes of photo repositories, into a shared album.

Then, getting ready for the memorial service became an hours-long exercise in looking at and talking and reminiscing about all the various moments with my dad captured on various devices over the years.

The act of looking at the photos – and recalling and sharing those occasions featuring my dad – with those around me, allowed us to celebrate a life, even as it allowed us to mourn.

Who knew that I would have Google Photos to thank for what turned out to be a bittersweet – more bitter and sad at this exact moment than sweet – time of remembrance.

Instagram and Contemporary Image

Back in 2011, when I started exploring visual communication and the impact of the image, I was introduced to scholar Lev Manovich, who has written prolifically about digital culture and new media. My particular interest at the time was about the image in digital culture, and how the internet and digital technology have impacted what we know as the photograph. While I read a lot about digital photography, the materiality of the image, and nature of the snapshot, I became obsessively interested in Instagram and the nature of social photography. Thus, my thesis topic in grad school became focused on particular aspects of Instagram. But some of my initial thoughts about the topic were influenced by Manovich’s writing.

Things come full turn. Six years later, it turns out that Dr. Manovich has written an entire book about Instagram.

This past October, WIRED posted a teeny piece entitled, “Prof. Lev Manovich publicly wondering if Instagram is photography.” The post mentioned Dr. Manovich’s book, Instagram and Contemporary Image. He has made the book available on his blog, under a Creative Commons license. The summary of the book reads:

Millions of people around the world today use digital tools and platforms to create and share sophisticated cultural artifacts. This book focuses on one such platform: Instagram. It places Instagram image culture within a rich cultural and historical context, including history of photography, cinema, graphic design, and social media, contemporary design trends, music video, and k-pop. At the same it uses Instagram as a window into the identities of first truly global generation connected by common social media platforms, programming languages, and visual aesthetics. The book demonstrates how humanistic close reading and computational analysis of large datasets can work together by drawing on the work in Manovich’s Cultural Analytics Lab with 16 million Instagram photos shared in 17 large cities worldwide since 2012.

I look forward to reading this newest Instagram study.

Plugging away this gorgeous spring

So…. I was derailed from my winter 2015 timeline because of broken ribs, my broken ribs (5 of them, 5!!). Totally out of left field, and about a month of pain and recovery. After that, it was about 3 weeks of getting into the rhythm of a (temporary) new position at my university, and then March came and I got back into writing up data findings.

Now, we’ve set a deadline, quickly approaching, to get this baby done. What this means is barricading myself from my house and my son, for increasing periods of time, to be able to write and organize, write and edit and rewrite, and organize and cut and write some more.

And it’s hard, when the neighbourhood looks like this:

Last year, I didn’t really give up things to try and work on grad studies. I leaped into new experiences and a wonderful Americana road trip and some tinkering with a new camera, and didn’t really FOCUS on getting school work done.

Last year, I didn’t really give up things to try and work on grad studies. I leaped into new experiences and a wonderful Americana road trip and some tinkering with a new camera, and didn’t really FOCUS on getting school work done.

But now I am doing what grad students have done since time immemorial – giving up parts of the fullest, most interesting, selfish life, in order to move forward and make progress in their studies.

Seattle and the northwest*

I recently returned from a visit to Seattle, Washington, about 6 hours by car from our town. The purpose of the trip was to investigate and document The Darkroom Series 3.0, a photo exhibit/show of northwest-based photographs taken solely on mobile phones. The show was held at Zeitgeist Coffee, near King Street Station in downtown Seattle. Part of my objective was to gauge the sense of the northwest* as expressed by mobile photographers and by residents, and also to gain a personal feeling and experience for myself.

Seattle is a city I’ve visited many many times – and I love it every visit. This time was no exception. In fact, not having been for over a year, I loved it more – the big city, the green spaces interspersed with the urban centre, the Pacific Ocean, the bustling creative markets and shops – these things felt like welcome to me, with its similarities to Vancouver, which I still miss since moving away.

So there was familiarity, but also a sense of freshness. This trip, I focused on what #northwestisbest might mean. This was the focus of the Darkroom show, and is the phenomenon that I’m looking at for my thesis. There is clearly a perspective of rural, landscape-based visual expression of the northwest, that might clash but somehow doesn’t, with a city-centred view of the northwest that I previously held. But there was a clearly contrasting (yet complementary) understanding of what the northwest means and looks like, for residents as well as expressed through public photo streams.

One of the strongest impressions I left with is the very vibrant community and activity around mobile phone photography in Seattle. They have Juxt, a very strong Instagram community, and a city news station and channel that itself is actively involved in and supportive of phone photography. These groups are key to the projects, meet ups and interactions of the public and very motivated, creative individuals centred around phone photography, resulting in palpable energy and creative work coming out of the northwest.

There is more, a lot more, that I experienced during my trip, but I’m still getting my head around it. I wish I could have had another month or two there! I’ll be returning in the next few weeks and look forward to seeing the city and surrounding areas, this time when its a bit warmer.

*Northwest is used here to denote the geographical region of Oregon and Washington, but according to the #northwest, #northwestisbest, #nw and #nwistbest tagged photos and posts on social networks, the term seems to indicate a much broader region extending from Northern California up through British Columbia to southern Alaska.

About selfies

I was surprised to see how much coverage and conversation took place over the selfie during the last quarter of this year. In just some of the New York publications, for example, that I browse, there were many posts on this subject: the article in the “News Analysis” section of the Times from October, James Franco in the Times just this week discussing why he would rather see an individual’s gallery include selfies than not have any at all, the mildly sensational New York Post post on the selfie-shot that caught a suicide-jumper in-action, and the New York Daily News mention and snapshot of President Obama caught mid-selfie-shot.

It was odd to see the media buzz and interest around something that has been around, well, forever. A fascinating example of a very well-done and interesting selfie gallery that’s been around for a long time and that has itself garnered some buzz over the years is that of Noah Kalina, in which he shares a shot of himself that he’s taken regularly, if not every day, since 2000.

It’s especially interesting how selfies have been taken up by teenagers all over the world – a public performance of self-identity and assertion shared on social networks, in photographic, and more recently, in video format. In all of the photo social networks I belong to or have at some point belonged to (PicPlz before its demise, Eyeem, Instagram, Meebo, LemeLeme, Kakao Story for example), there are countless selfies in the public and private photo streams, noticeably by teens and mid-twenty-somethings who regularly document and post images of themselves, whether the images capture their outfits, their nails, and/or their faces.

I, too, participate in taking pictures of myself, though I don’t share them to a public stream. Rather, I own a very simple app called Everyday, launched in March 2011, whose sole purpose is to allow you to take selfies and then compile them into a time-lapse video, should you wish. Thus, I have a personal gallery of shots of my face that I have taken since October 2011 (when I first purchased an iPhone).

There is the question of WHY so many people indulge and practice taking pictures of themselves, and more recently, posting the pictures to one’s various public and private networks. It’s been discussed plenty on the internet recently (just Google “selfie”) but the point that stands out for me is that advances in technology and software, and the always-on connection to the internet makes possible the fulfilment of people’s secret desire(s) to seen, recognized and known through a visual performance that is vaguely narcissistic and expressive. There’s a whole master’s thesis that can be written on that topic, for sure.

___________

Once in a while, one comes across something very stirring and humane in a self-portrait series. I was recently reminded me of a series of self-shot portraits I came across on Tumblr by artist Sophie Starzenski. It’s a unique chronicle of her pregnancy and a very interesting and beautiful version of the selfie.

On the Constant vs Decisive Moment

Came across this post today, on the “Constant Moment” vs. the “Decisive Moment.

Author Clayton Cubitt describes the Decisive Moment as “the creation of art through the curation of time.”

But technological development and commercial hardware has made possible the capture of moments, from all angles, at all times, connected constantly with a stream of viewers/commenters/information channels. Cubitt suggests that while such capture of moments is not new to photography, what has emerged is the Constant Moment, which in photography can be understood as viewing and capture that is “as close to a time machine” as we are likely to get, where what has been captured can be seen forward and backwards, from any which angle, and where in it is captured the “billion missed Decisive Moments that previously slipped through our fingers.”

Instagram, still thriving

There has been no other online photographic community that has utilized the mobile platforms made so widespread by Apple and by various Android handsets so well as Instagram.

For all the furor earlier this year over Instagram’s terms of service regarding user’s photographs and rights, resulting in droves of users leaving Instagram and seeking other social online communities centred around photography, no other photographic platform has reached the level of community engagement and viewership that Instagram has achieved, and continues to grow, in its short life. Yes, Flickr has caught on, finally, with a worthy mobile app, but that community was born on the desktop web and only recently been really taken off as a mobile-accessed community (though it’s interesting that according to Flickr’s own camera use statistics, even lacking a decent mobile app until earlier this year, the most “popular camera” in the Flickr community since the summer of 2011 has been the iPhone).

For all the furor earlier this year over Instagram’s terms of service regarding user’s photographs and rights, resulting in droves of users leaving Instagram and seeking other social online communities centred around photography, no other photographic platform has reached the level of community engagement and viewership that Instagram has achieved, and continues to grow, in its short life. Yes, Flickr has caught on, finally, with a worthy mobile app, but that community was born on the desktop web and only recently been really taken off as a mobile-accessed community (though it’s interesting that according to Flickr’s own camera use statistics, even lacking a decent mobile app until earlier this year, the most “popular camera” in the Flickr community since the summer of 2011 has been the iPhone).

I’ve shared in another post about grappling with my own guilt about staying with Instagram after the appalling terms they released (then shortly amended) after they were acquired by Facebook. That’s not to say I didn’t look at alternatives to Instagram (the top app and community that comes to mind, that is thriving today and a great place to discover great photographers, is EyeEm) but after investing time, history and after finding community members whose photographs and eye I admired and thus followed, it was really hard to switch to another platform when all the good stuff of Instagram – the people, the comments, the conversations, the photos – rested within the Instagram community (the same rationale goes to why it’s hard to switch from Facebook to Google+). I’ve noticed that 3 Instagram community members I followed stopped sharing photographs altogether on Instagram at that time – but their accounts are still active today and they didn’t delete their profiles. Why? My guess is that though they moved to other sharing communities (I know two switched to Path, and another is now primarily active on 500px, and all of them remain active on Flickr) they remained on Instagram because some of the people they followed didn’t leave, and they wanted to remain in touch with them and continue to view and comment on their photographs.

Anyway, I’m fascinated by the mobile-to-life connections that Instagram and Instagram-inspired photo projects (such as Instameets) have fostered. The idea that a little app on the iPhone or Galaxy S2 makes possible a real life social gathering and connection between a group of strangers, motivated by a shared love of photography and visual capture, all over the world, is pretty incredible.

Yesterday a post about filmmaker Paul Tellefsen’s senior year project that turned into a full-fledged short film popped up in my feed. The film is called “Instagram Is” and it’s an interesting look at what Instagram means to some people, and a glimpse into what an Instagram-centred community looks like. It also shows what people in this community actually do.

Photographing Renaissance portraits: rethinking identity & culture

Here is a fantastic project that rethinks classical Renaissance paintings in order to counter current European xenophobia, according to this article in The Atlantic by Rebecca Rosen.

Artist Mark Abouzeid recreates the backdrop and subjects of classical paintings with real people posed and photographed as his resulting work.

Abouzeid calls his project project “The New New World” and Rosen describes it thus:

a series of portraits of modern-day, immigrant Florentines, placed into the poses, costumes, and props of classic Florentine paintings. The idea wasn’t to copy the originals — if that’s what he had wanted, he could have done so much more easily and with much more exacting results in Photoshop — he explained to me over email, but “to renew these subjects in a way to confront them with their predecessors.” By placing these extracomunitari into the artistic and material representation of Italy, he could make them a part of it.

Left: Lorenzo il Magnifico (1449 -1492), by Agnolo di Cosimo detto il Bronzino, 1565-1569. Right: Dre Love, originally of Queens, New York. (Mark Abouzeid)

The project reminds me, at least in the aesthetics, of the work of Australian photographer Bill Gekas, whose stunning photographs of his daughter posed in imitation of paintings of old masters have garnered praise and media attention.

I love that contemporary photographers can and continue to find powerful inspiration from art works created hundreds and hundreds of years ago. But more importantly, I love that artists like Mark Abouzeid can speak powerfully against existing racial fears and undercurrents in his (and the larger) world through his creative work.

Smartphone photography innovates

Back in 2011 and then at CES (Consumer Electronics Show) 2012, I remember hearing about a new kind of camera in the works, one that would have software connecting it to the internet (this was not very surprising news) AND running a mobile operating system (in this case, Google’s Android OS) that would enable users to put apps on the camera, most likely for photo editing and social sharing. The second is what was surprising.

A camera that now comes bundled with a (smartphone) operating system?

Well, mobile operating systems have not only run on smartphones: the Palm Pre, the iPod Touch and handheld gaming systems are examples of this. But it IS the smartphone (iPhone, and all the Android ones since) that has harkened a shift in the way photographs are being taken, edited, created and then distributed on the web and in social networks. In particular, I note the rise of a particular app culture around photo editing at one’s fingertips, and the ability to instantly share, view and comment on photographs as two distinctive features of this “shift.”

And that whole shift has trickled back to a culturally and economically driven development in technology that has seen the introduction of this digital camera (no longer a mobile camera phone only) that is “connected.” The above product photographs of the Samsung Galaxy Camera (latest in the Samsung Galaxy line, following the Galaxy phone, Galaxy tablet, and Galaxy media player) is a case in point. (My favorite, the Polaroid Smart Camera, hasn’t yet seen the light of day).

I came across this neat little discussion on mobile phone photography community AMPt’s user form page, asking whether or not these new internet connected cameras should be considered “an acceptable device in mobile photography?”

The main question aside (my immediate reaction is, of course, YES – it’s “mobile”, isn’t it?), what I learned on the thread is that there is a new hashtag kicking around on the net denoting pictures taken on these new Samsung Galaxy Cameras: #galaxycamera. I checked it out on Flickr, and yes, indeed, there are already many photos kicking around there, and on Instagram, with this particular tag.

I think it’s an odd device, and not really destined for mobile stardom: too little for really terrific photos, too slow for app enthusiasts, and just extraneous for people who use their phones because they’re already carrying it around. However, I do wish these newfangled gadgets will find their niche market: maybe it’ll be people who don’t want to be tied to smartphones or phone contracts but do wish for the ease and immediacy of snapping, editing and sharing pictures on the go.

This gadget has caught my attention because it is a notable indication of the direction that mobile phone photography has helped shape and develop. I should add to this last statement that specifically, it is the direction that mobile phone photography advocates and users have helped shape and promote.

Just as community buzz and support and enthusiasm revived the lifespan of Polaroid-type film technologies, so also have they spurred on this next step in the development and history of mobile photography.

Getting down to the nitty gritty, or, the research method

Since my key research interest lies in what mobile phone camera users are doing with their phone photographs and how their practices relate to space (in the expanded sense of mental, local, glocal, social space) and place, my mind was set months ago that the approach best-suited to understanding user motives, practices and perceptions would be ethnography.

And as I expressed a few months back, ethnography is SO broad, so widely used in research in so many disciplines, that it was hard to narrow down what sort of ethnography would be suitable to my own project. There were, and are, so many books, articles and definitions of ethnography that I was dizzy trying to select one approach, fearing making the wrong choice in case I missed one or another suitable method.

I recently picked up a book by cultural geographer, Mike Crang, who has done a lot of work in tourism, virtual space, place, and city technology infrastructures. His book, Doing Ethnographies, has been very helpful in getting a sense of ethnography applicable to my particular proejct.

Highly recommended.